Learning something new deserves all your attention.

Sometimes, distractions are a good thing.

Sometimes, distractions are a good thing.

Like listening to your iPod during a dentist appointment or going for a run to get your mind off tomorrow’s big presentation.

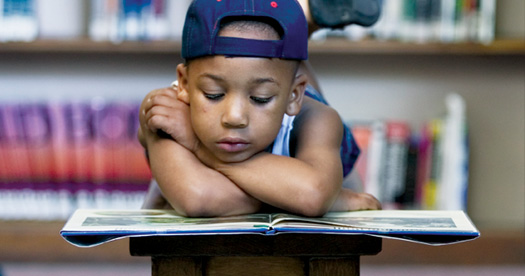

But at other times, you need your brain to be focused on one thing, and one thing only if you’re going to do it right. One of those times is when you’re trying to learn something new.Whether a student is in college or kindergarten, whether they’re extremely focused or have the attention span of a kitten, virtually any external stimulus can nudge them off course – especially if that course requires all of their brain power, like math, reading or philosophy.

So what happens when we give them a tool that can help them learn but at the same time offers them the mother of all distractions – the Internet? Can a student resist the temptations of email, games and the Web on their laptop to concentrate on a lecture – an issue that doesn’t come up when taking notes on paper? And what about learning to read on an eReader? Can technology be more helpful than printed books in teaching kids the first of those “three Rs”?

These questions are being hotly debated by educational experts around the world, which have seen a dramatic rise in the number of students of every age using technology for learning. In some cases, the practice has been encouraged through programs like One Laptop per Child or university-driven laptop initiatives. But to the dismay of many proponents of the computer as the great educational enabler, researchers are finding they can actually interfere with students’ ability to learn in certain contexts.

A study conducted at Duke University revealed that students in grades five through eight tend to post lower math and reading scores after they obtain a computer at home.1 Kids from disadvantaged families seem to be particularly impacted since, as researchers suggest, their parents may not monitor computer use as closely to ensure they are not getting sidetracked from their studies by playing games, emailing or surfing the net for fun. Professor Jacob Vigdor, who co-conducted the study, pointed out that while “adults may think of computer technology as a productivity tool first and foremost… the average kid doesn’t share that perception.” 1

Early education specialist Lisa Guernsey takes this notion of “digital distraction” in kids and applies it to the use of eReaders during story time.2 The bedtime story has been instilling a passion for learning and reading in kids for time immemorial. Guernsey argues that the use of a tablet as opposed to a printed book not only changes the dynamic between the parent and child, it shifts the focus from reading to learning to how use the technology. The conversation sounds more like “Push here to turn the page” than “What do you think will happen next?”

Ms. Guerney further observes that children whose parents talk to them about what they’re reading gain reading skills faster, and that children reading with parents from digital rather than physical books aren’t getting as much of that kind of interaction.

Another study, conducted by Carrie Fried of the Winona State University Psychology Department3, has proven that preschoolers and young children aren’t the only ones whose attention can get diverted by technology. A semester-long research project conducted within her own faculty revealed that the college students in that class multitasked for an average of 17 minutes out of each 75-minute period, with 81% reporting that they checked email, 68% used instant messaging, 43% surfed the Net, 25% played games, and 35% did “other” activities. It also showed that the more the students used a laptop in class, the lower their class performance.

In her paper, Fried cites numerous cognition experts who agree that attentional shifts and information overload – such as those provided by use of the Web during a course – can interfere with learning. And that’s why a growing number of professors whose courses are not specifically designed to promote technology use for in-class interaction are banning laptops from their classroom. Some are so passionate about it that they disconnect the room’s Wi-Fi for the duration.

Interestingly, it was demonstrated that laptops also distract the students sitting next to the user. In fact, the results indicated that laptop use by fellow students was the single most reported distracter among survey participants, accounting for 64% of all responses. Not to belabor a point, but a pad of paper has rarely distracted your neighbor in class. And probably the worst it can do for you is tempt you into a few doodles in the margins.

Computers are wonderful, indispensible things. No question there. But they can sidetrack even the best of us from the task at hand, precisely because they have so much to offer. The printed word – whether you’re jotting down notes yourself or reading from a book – can offer you just as many rewards. Plus, while there’s no guarantee you won’t indulge in a daydream or two, it can help keep you focused on filling your brain.

** To read more about how you learn better on paper, go to: It’s easier to learn on paper.

1 Children with home computers likely to have lower test scores, Duke University Study. Duke Today. 2 Dell’Antonia, KJ, Why Books Are Better Than e-Books for Children, newyorktimes.com, December 28, 2011.Domtar Paper provided content and image.